Sometimes grapes are grown in unexpected places, and island wines are worth seeking out. After all, the purpose of a grape is to entice animals and birds to eat them and spread the seeds, which are largely undigested, to other areas keeping the vines alive. Since birds enjoy grapes, the vines can easily spread to unique areas around the world. Birds and other animals do not spread the seeds of grapes around in unison to create vineyards, rather that is done by people, and people have spread the vine for centuries. Some of the places that vines exist seem unusual to us now but were once important trade routes. Because of the trade routes of the past, many islands that are hospitable to grapes make wine.

Islands can be difficult to get to, and they can feel removed from the hustle and bustle of daily life. The typical allure of visiting islands is going for relaxation and vacation, a place to get away from it all. There is often a focus on the island’s natural resources in everyday life, as anything that does not come from the island has to be imported which drives up costs, can have time delays, and items may not be regularly available. Plus, any island on a trade route was a place for refueling and restocking the ship. It is no wonder that many islands make their own alcohol, and the islands of Portugal are no exception.

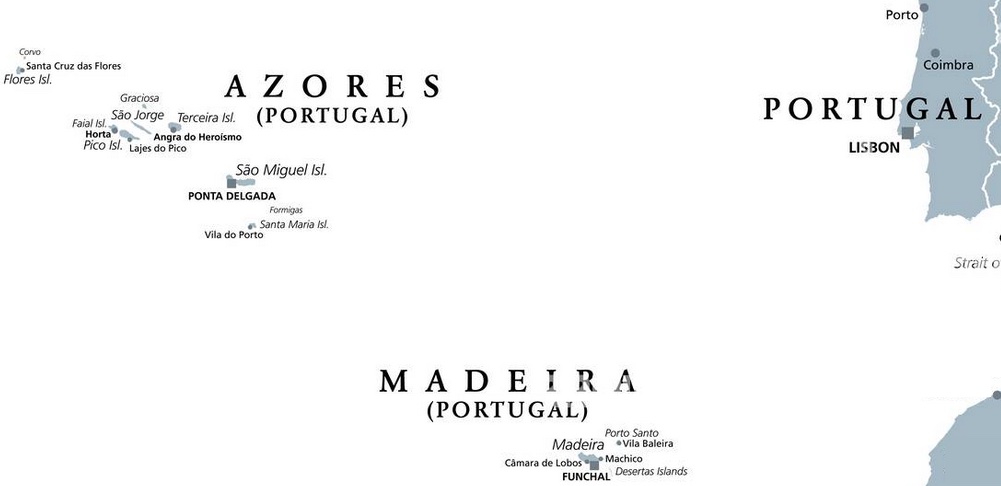

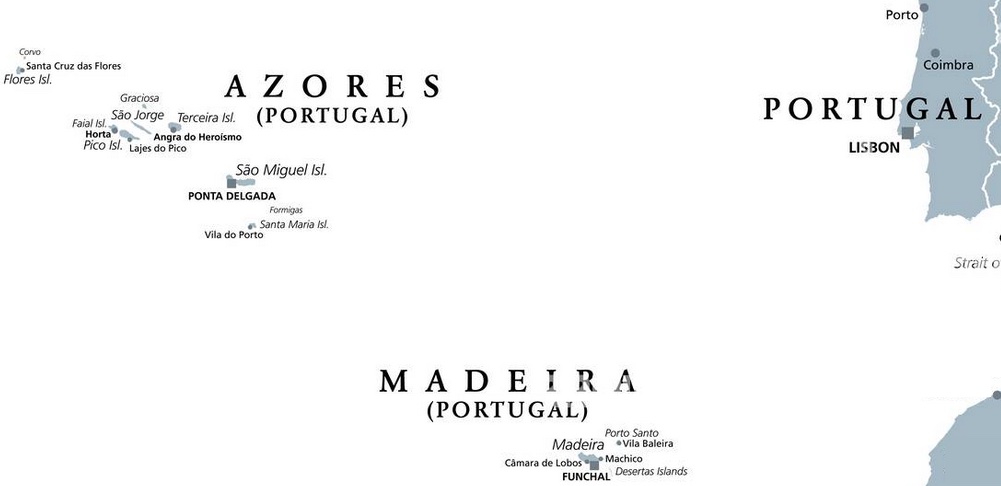

Portugal has two archipelagos, or groups of islands, Madeira and Azores (Açores). Each archipelago was important on trade routes when goods were moved throughout the world on ships. Since the invention of air travel and heightened speed of ships, both island groups have become less of a port of call, yet both groups of islands make still and fortified wines. Understandably when these islands were stops on trade routes, fortified wines were of considerable importance. The fortification process of adding higher proof alcohol to wine stabilizes it and protects the wine from spoilage. While the fortified wines are often the most well-known, the still, dry non fortified wines are also worth some attention.

Azores or Açores, the latter being the Portuguese spelling, is a collection of nine islands in the Northern Atlantic Ocean between Portugal and North America. They are volcanic in origin and the natural beauty can make it feel as if transported to a different era. Some areas look prehistoric, like something from the time of dinosaurs. Of the nine volcanic islands three of the islands make wine. Each island has its own DOP (Denominação de Origem Protegida) also known as a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO). There is also an overarching Azores Vinhos Regional (VR). There is a focus on white wine in the region, but some red wines are made as well. One look at some of the vineyards in this region can make a person question how vines even came to be in this place, as planting vines here was no easy task.

Vines on a cliff wall

The answer to the question of how vines came to Acores is unclear. Some believe it was missionaries and/or monks that brought vines from Madeira, some believe the settlers brought vines with them, and yet others believe that Henry the Navigator brought vines from Crete. The three islands which produce wine are Pico, Terceira, and Graciosa. Regardless of how the vines reached the islands, the hard work put into creating vineyards was done by the island inhabitants. The volcanic rock had to be unearthed to allow vineyards to be planted, and what was removed from the ground was stacked into basaltic rock walls known as currais on the island of Pico. The currais protect the vines from wind, sea spray, and retain heat from the sun that is released in the evening, helping the grapes to ripen. On Pico, the vines are planted in the cracks in the rocks that sometimes had to be scraped and widened to allow plantings, while soil was brought in from a neighboring island to help stabilize the vines within the rocks. This area is a UNESCO world heritage site. Most of the wine made under the Pico DOP is Arinto do Açores which is a synonym of Sercial from Madeira or Esgana Cão. This grape is sometimes called the dog strangler because of its high amount of acidity. The island of Terceira produces wine under the Biscoitos DOP which got its name from the volcanic rocks that look like biscuits. The wines of Biscoitos are typically made from Verdelho. The third island and DOP is Graciosa, and only small quantities of wine come from this location. Each DOP covers white, sparkling, and fortified wines; for red wines look for the Azores Vinho Regional or IGP labeling. There are limited quantities of these wines, they are not always the easiest to find, and do not expect them to be inexpensive just because they are from a lesser-known region. The white wines are known for their bright acidity with a touch of saline, while the reds are light and bright and from a mix of grapes that generally do not see oak.

Madeira is a collection of four islands, Madeira, Porto Santo, Desertas, and Selvagens, with the two former making wine. The islands are in the Atlantic Ocean closer to Morocco than Portugal. While grapes are grown on both islands, more wine is made and exported from the island of Madeira. Madeira was at one time an incredibly important port along the trade route, and now it is more often a port for small cruise ships. The island was built by a series of volcanic eruptions, the soil is fertile, and the land is steep. Poios, or small terraces, carved from the bedrock of grey or red basalt were created to stop the soil from eroding during heavy rainfall and to keep the vines in place. The vineyards of Madeira are small, owned by growers, and are all over the island. The average vineyard size is .23 hectares and most wineries have very little vineyards of their own. While the Fortified wines that contain the namesake Madeira are their best known wines, the amount of still wine sold as Madeirense DOP is growing. The wines are made in red, white, and rose styles; these wines are mainly made from indigenous Portuguese grapes but even Cabernet Sauvignon has found its way here, though it does struggle to ripen. Typically, a grower can make more money selling grapes for non-fortified wines, but the ripeness level needs to higher. A minimum of 10.5% alcohol is needed for white and rose with a minimum of 11.5% for reds. This is a sharp contrast to the minimum of 9% required at harvest for grapes being used for fortified wines. As the trend for sweet, fortified styles of wine continues to decline, more companies are making both fortified and non-fortified wines. The most promising grapes for still, unfortified wines are made from Verdelho and Sercial. The low pH of the worn and weathered basalt soils creates grapes with high acidity levels, keeping wines refreshing and zippy when not tamed by sugar.

The still, white wines of the Islands of Portugal share volcanic soils, labor intensive work, and occasionally the same grapes, despite being 900km apart. Areas that would be unhospitable for almost any other crop are making exceptional wines. The unfortified wines may not have the historical significance or the long rich history, but these wines do have the refreshing acidity and freshness that comes from vines growing in the rocks.